Part III

Substantive Law

- 12. Limiting Powers: EU Fundamental Rights

- 1. Constitutional History: From Paris To Lisbon

- 13. Free Movement: Goods I—Negative Integration

- 2. Constitutional Nature: A Federation Of States

- 14. Free Movement: Goods II—Positive Integration

- 15. Free Movement: Persons—Workers and Beyond

- 16. Free Movement: Services and Capital

- 3. Governmental Structure: Union Institutions I

- 17. EU Competition Law: Private Undertakings

- 18. EU Internal Policies: An Overview

- 4. Governmental Structure: Union Institutions II

- 19. EU External Policies: An Overview

- 20. Epilogue: Brexit and the Union: Past, Present, Future

- 5. European Law I: Nature—Direct Effect

- 21. Appendix: How to Study European Law

- 7. Legislative Powers: Competence and Procedures

- 8. External Powers: Competence and Procedures

- 6. European Law II: Nature—Primacy/Pre-emption

- 9. Executive Powers: Competence and Procedures

- 10. Judicial Powers I: (Centralized) European Procedures

- 11. Judicial Powers II: (Decentralized) National Procedures

- 22. Extra chapter: Competition Law II: State Interferences

Introduction

From the very beginning, the central task of the European Union was the creation of a ‘common’ or ‘internal’ market. This is ‘an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured’. The Union’s ‘internal market’ would thus comprise four fundamental freedoms and involve ‘the elimination of all obstacles to intra-[Union] trade in order to merge the national markets into a single market bringing about conditions as close as possible to those of a genuine internal market’.

The economic advantages of uniting various national markets into a common market are manifold. Economic growth and efficiency gains will result from a better division of labour between nations through which comparative advantages can be exploited. States have however not unconditionally followed the promises of free trade in the past. On the contrary, the better part of the history of Europe is a history of economic ‘nationalism’. Each State has been ‘protective’ of its own national economy and erected trade barriers, such as ‘customs duties’ or ‘quantitative restrictions’. The elimination of such national ‘protectionism’ was the primary aim behind the creation of the EU ‘internal market’.

How could the Union create a ‘single’ internal market out of ‘diverse’ national markets? To create a common market, the EU Treaties pursue a dual strategy: negative and positive integration.

The Union was first charged to ‘free’ the internal market from unjustified national barriers to trade in goods, persons, services and capital; and, in order to create these four ‘fundamental freedoms’, the Treaties contained four prohibitions ‘negating’ illegitimate obstacles to intra-Union trade. This strategy of negative integration is complemented by a – second – strategy: positive integration. The Union is here charged to adopt positive legislation to remove obstacles to intra-Union trade arising from the diversity of national legislation. For that purpose, the Treaties conferred a number of legislative ‘internal market’ competences to the Union. The most general of these competences can be found in Title VII of the TFEU; and the most important provision here is Article 114, which entitles the Union to adopt harmonisation measures that ‘have as their object the establishment and functioning of the internal market’. The EU Treaty provisions governing the internal market are set out in Table 13.1.

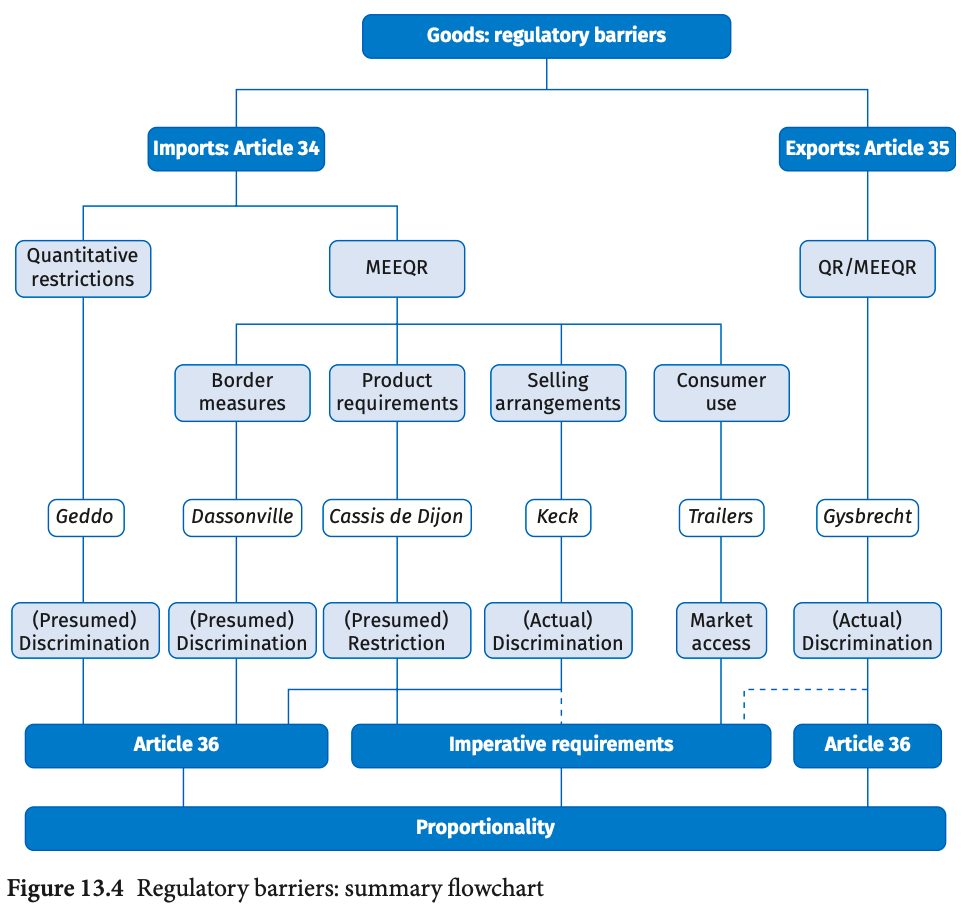

Chapters 13 and 14 will, respectively, explore the spheres of negative and positive integration in the context of the free movement of goods. The free movement of goods has traditionally been the most important fundamental freedom within the internal market. Chapter 13 here analyses the constitutional regime of ‘negative integration’; and in many respects, that regime has been ‘path-breaking’. It has for a long time provided the general ‘model’ that would be followed by the other three freedoms. Section 1 therefore uses the free movement of goods provisions to introduce and present the general jurisdictional problems governing all (!) four fundamental freedoms and the ‘structure’ of negative integration generally.

Sections 2–4 subsequently concentrate on the specific substantive regime for goods. This regime is – sadly – split over two sites within Part III of the TFEU (see Table 13.2). It finds its principal place in Title II governing the free movement of goods, which is complemented by a chapter on ‘Tax Provisions’ within Title VII. With regard to goods, the Treaties expressly distinguish between fiscal restrictions and regulatory restrictions. Section 2 deals with fiscal restrictions, that is: pecuniary charges that are specifically imposed on imports. By contrast, regulatory measures are measures that limit market access by ‘regulatory’ means, and section 3 explores the multitude of possible regulatory restrictions, such as product requirements. Section 4 finally looks at possible justifications for such regulatory restrictions.

Cases

Legislation

EU Directives

Commission Directive 70/50/EEC of 22 December 1969 based on the provisions of Article 33(7), on the abolition of measures which have an effect equivalent to quantitative restrictions on imports and are not covered by other provisions adopted in pursuance of the EEC Treaty, [1970] OJ L 13/29

Directive 2008/95/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 22 October 2008 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks, [2008] OJ L 299/25 (Trade Mark Directive 2008)

Figures

Extra Materials

Useful Videos

Useful websites

Further Reading

Books

F. Amtenbrink et al. (eds), The Internal Market and the Future of European Integration: Essays in Honour of Lawrence W. Gormley (Cambridge University Press, 2019)

C. Barnard, The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms (Oxford University Press, 2013)

L. Gormley, EU Law of Free Movement of Goods and Customs Union (Oxford University Press, 2009)

D. T. Keeling, Intellectual Property Rights in EU Law, I: Free Movement and Competition Law (Oxford University Press, 2003)

N. Nic Shuibhne, The Coherence of EU Free Movement Law: Constitutional Responsibility and the Court of Justice (Oxford University Press, 2013)

P. Oliver (ed.), Oliver on Free Movement of Goods in the European Union (Hart, 2010)

M. Poiares Maduro, We the Court: The European Court of Justice and the European Economic Constitution (Hart, 1998)

R. Schütze, From International to Federal Market: The Changing Structure of European Law (Oxford University Press, 2017)

J. Snell, Goods and Services in EC Law: A Study of the Relationship between the Freedoms (Oxford University Press, 2002)

A. Tryfonidou, Reverse Discrimination in EC Law (Kluwer, 2009)

S. Weatherill, The Internal Market as a Legal Concept (Oxford University Press, 2017)

Articles

A. Arena, ‘The Wall Around EU Fundamental Freedoms: The Purely Internal Rule at the Forty-Year Mark’ (2019) 38 YEL 153

R. Barents, ‘Charges of Equivalent Effect to Customs Duties’ (1978) 15 CML Rev 415

D. Chalmers, ‘Free Movement of Goods within the European Community: An Unhealthy Addiction to Scotch Whisky?’ (1993) 42 ICLQ 269

M. Danusso and R. Denton, ‘Does the European Court of Justice Look for a Protectionist Motive under Article 95?’ (1990) 17 Legal Issues of European Integration 67

A. Easson, ‘Fiscal Discrimination: New Perspectives on Article 95 of the EEC Treaty’ (1981) 18 CML Rev 521

A. Easson, ‘Cheaper Wine or Dearer Beer? Article 95 Again’ (1984) 9 EL Rev 57

S. Enchelmaier, ‘“Moped Trailers”, “Mickelsson & Roos”, “Gysbrechts”: The ECJ’s Case Law on Goods Keeps on Moving’ (2010) 29 YEL 190

R. Schütze, ‘Of Types and Tests: Towards a Unitary Doctrinal Framework for Article 34 TFEU?’ (2016) 41 EL Rev. 826

J. Snell, The Notion of Market Access: A Concept or a Slogan?’ (2010) 47 CML Rev 437

E. Spaventa, ‘Leaving Keck Behind? The Free Movement of Goods after the Rulings in Commission v. Italy and Mickelsson and Roos’ (2009) 34 EL Rev 914

M. Szydło, ‘Export Restrictions within the Structure of Free Movement of Goods: Reconsideration of an Old Paradigm’ (2010) 47 CML Rev 753

S. Weatherill, ‘After Keck: Some Thoughts on How to Clarify the Clarification’ (1996) 33 CML Rev 885

E. White, ‘In Search of the Limits of Article 30 of the EEC Treaty’ (1989) 26 CML Rev 235

How to Find (and Read) the EU Treaties

The EU Treaties constitute the primary law of the Union. The formula the ‘EU Treaties’ or simply ‘the Treaties’ commonly refers to two Treaties: the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

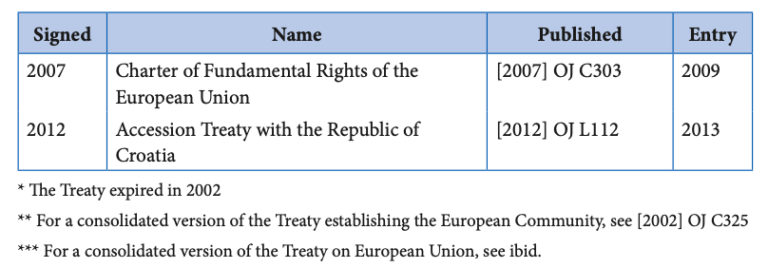

The ‘Treaties’ are the result of a long ‘chain novel’ of consecutive treaties (see Table 20.1). They started out from three ‘Founding Treaties’ that created the European Coal and Steel Community (1951), the European Atomic Energy Community (1957) and the European (Economic) Community (1957). A myriad of subsequent ‘Amendment Treaties’ and ‘Accession Treaties’ gradually changed the textual basis of the three Communities significantly; and this first treaty base would be complemented by a second treaty base in 1992, when the Maastricht Treaty created the (old) European Union.

To simplify the – very complex – textual foundations of the old European Union and European Communities Treaties, the Member States tried to create a single treaty in the early 2000s. The 2004 Constitutional Treaty was indeed intended to repeal all previous treaties; and it was to merge the European Union with the European Communities. Yet the attempt to ‘recreate’ one Union, with one legal personality, on the basis of one treaty failed; and the Member States thereafter resorted to yet another ‘Amendment Treaty’: the 2007 Reform Treaty – also called the Lisbon Treaty.

Despite its modest name, the Lisbon Treaty constitutes a radical new ‘chapter’ in the Union’s constitutional chain novel. For while it formally builds on the original ‘Founding Treaties’, it has nonetheless ‘merged’ the old ‘Community’ legal order with the old ‘Union’ legal order into a new ‘Union’ legal order.

Nevertheless, unlike the 2004 Constitutional Treaty, the 2007 Lisbon Treaty has not created a single treaty base for the European Union. Instead, it recognises the existence of two (main) treaties: the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The division into two EU Treaties thereby follows a functional criterion: the Treaty on European Union (TEU) contains the general provisions defining the Union, while the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) contains the specific provisions with regard to the Union institutions and policies. One of the new features of the post-Lisbon era is the possibility of minor treaty amendments instigated by European Council Decisions.

In addition to ‘Amendment Treaties’ there are now also ‘Amendment Decisions’ adopted by the European Council (see Table 21.4). The EU Treaties can today be found on the European Union’s

EUR-Lex website: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/collection/eu-law/treaties.html, but there are also a number of solid paper copies such as Blackstone’s EU Treaties & Legislation or my own EU Treaties and Legislation collection. What is the structure of today’s EU Treaties? The structure of the TEU and TFEU is shown in Table 20.4. The (longer) TFEU is divided into ‘Parts’ – ‘Titles’ – ‘Chapters’ – ‘Sections’ –‘Articles’, while the (shorter) TEU only starts with a division into ‘Titles’. The EU Treaties are joined by numerous Protocols and the ‘Charter of Fundamental Rights’. According to Article 51 TEU, Protocols to the Treaties ‘shall form an integral part thereof’; and the best way to make sense of them is to see them as legally binding ‘footnotes’ to a particular article or section of the Treaties.

By contrast, the Charter is ‘external’ to the Treaties; yet it also has ‘the same legal value as the Treaties’.

How to Find (and Read) EU Secondary Law

The Union publishes all of its acts in the Official Journal of the European Union. Paper versions can be found in every library that houses a ‘European Documentation Centre’, but electronic versions are also openly available on the Union’s EUR-Lex website: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/oj/direct-access.html. The Union distinguishes between two Official Journal series: the L-series and the C-series. The former contains all legally binding acts adopted by the Union (including its international agreements), while the latter publishes all other information and notices. Originally, only the paper version of the Official Journal was ‘authentic’; but since 1 July 2013, electronic versions of the Official Journal (e-OJ) are equally authentic and therefore endowed with formal legal force.

Union secondary law will first mention the instrument in which it is adopted. It will typically have the form of a ‘Regulation’, a ‘Directive’ or a ‘Decision’. This will be followed by two figures. In the past, where the Union act was a regulation, the figure was: number/year; while for directives and decisions this was inversed: year/number. However, since 2015, this has changed and all main Union instruments are now arranged by year/number.treaty base would be complemented by a second treaty base in 1992, when the Maastricht Treaty created the (old) European Union.

Where the year and number are known for a given EU act, the easiest way to find it is to use the Union’s EU-lex search engine: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html. Importantly, there may be two or more acts for a given number combination, especially where a ‘legislative’ act has been followed by a non-legislative act. For two types of non-legislative acts – namely: ‘delegated’ and ‘implementing’ acts – the EU Treaties require that they contain the word ‘delegated’ or ‘implementing’ in their title. This is to indicate – at first glance – that these executive acts have been adopted according to a particular decision-making procedure. States thereafter resorted to yet another ‘Amendment Treaty’: the 2007 Reform Treaty – also called the Lisbon Treaty.

What is the structure of a piece of Union legislation? After its ‘Title’ there follows a brief summary of the decision-making procedure that led to the adoption of the act – including a reference to the legal competence on which it was based. Thereafter comes the ‘Preamble’, which sets out the reasons for which the Union act has been adopted. The content of the act is subsequently set out in various ‘articles’, which may be grouped into ‘Sections’ and ‘Chapters’. For very technical Union legislation, there may also be an Annex – which, like a ‘Schedule’ in a UK statute, adds detailed provisions ‘outside’ the core content of the act. To illustrate this legislative structure, let us take a closer look at the Services Directive as it would be published in the Official Journal.

How to Find (and Read) EU Court Judgments

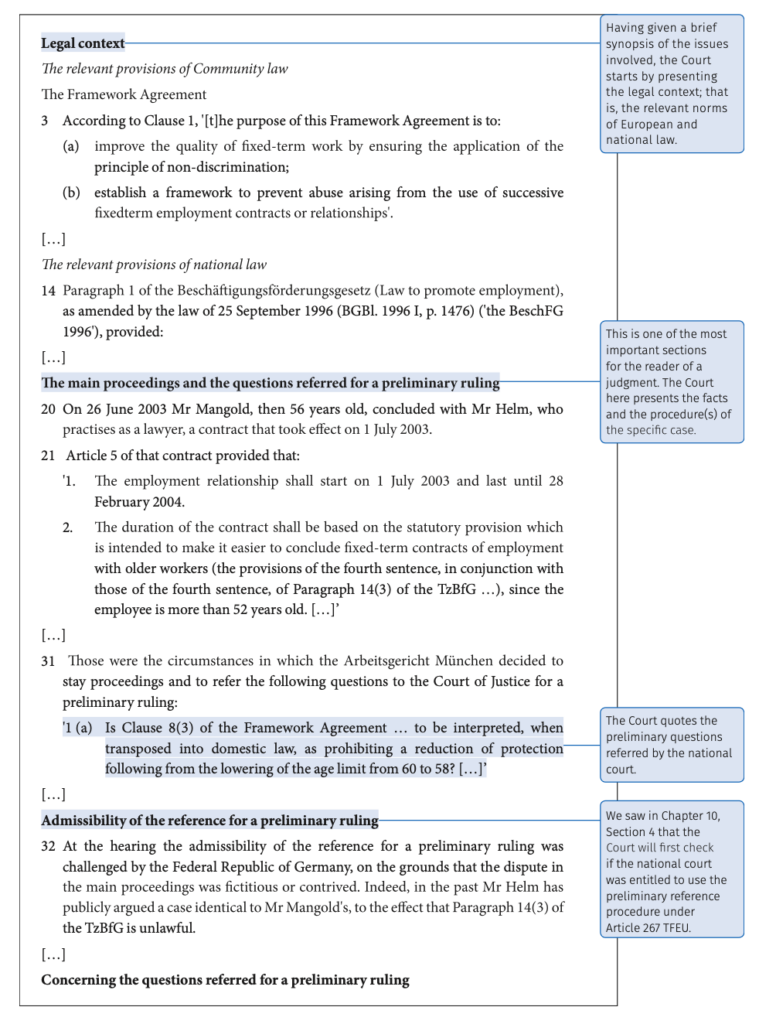

All EU cases are identified by a number/year figure. Cases before the Court of Justice are preceded by a C-, while cases decided before the General Court are preceded by a T-( for the French ‘Tribunal’).7 The Civil Service Tribunal prefixed its cases with an F-( for the French ‘Fonction publique’). Following this unique figure come the names of the parties to the case. A full case name would for example be: Case C-144/ 04, Werner Mangold v. Rüdiger Helm. However, since no one can remember all the numbers or all the parties, EU cases often get simply abbreviated by the main party; in our case Mangold.

In the past, judgments of all EU Courts were published in paper form in the purple-bound European Court Reports (ECR). Cases decided by the Court of Justice were published in the ECR-I series; cases decided by the General Court were published in the ECR-II series, while cases decided by the Civil Service Tribunal were published in the ECR-SC series. However, as of 2012, the entire Court of Justice of the European Union decided to go ‘paperless’ and it now publishes its judgments only electronically.8 The two principal websites here are the Court’s own curia website (http://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/j_6), and the Union’s general EUR-Lex website (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html). For the purposes of this book, the easiest way is however to go to www.schutze.eu, which contains all the judgments mentioned in the main text – including the ‘Lisbon’ version of all classic EU Court judgments.

Once upon a time, judgments issued by the European Court were – to paraphrase Hobbes –‘nasty, brutish and short’. Their shortness was partly due to a structural division the Court made between the ‘Issues of Fact and of Law’ (or later: ‘Report for the Hearing’), which set out the facts, procedure and the arguments of the parties, on the one hand, and the ‘Grounds of Judgment’ on the other. Only the latter constituted the judgment sensu stricto and was often very short indeed. For the Court originally followed the ‘French’ ideal of trying to put the entire judgment into a single ‘sentence’! A judgment like Van Gend en Loos contains about 2,000 words – not more than an undergraduate essay.

This world of short judgments is – sadly or not – gone. A typical judgment issued today will, on average, be four to five times as long as Van Gend. (And in the worst-case scenario, a judgment, especially in the area of EU competition law, may be as long as 100,000 words – a book of about 300 pages!) This new comprehensiveness is perhaps the product of a more refined textualist methodology, but it also results from a change in the organisation and style of judgments. Modern judgments have come to integrate much of the facts and the parties’ arguments into the main body of a ‘single’ judgment, and this has especially made many direct actions much longer and much more repetitive! The structure of a modern ECJ judgment given under the preliminary reference procedure may be studied by looking at Figure 20.2.

How to Find EU Academic Resources

The literature with regard to European Union law has exploded in the last 30 years. Today, there exists a forest of European law journals and generalist textbooks. Moreover, since the mid 1990s ‘European’ law has increasingly developed specialised branches that are sometimes even taught separately at university (as is the case at my own university). The three main branches here are: European constitutional law, European internal market law and European competition law. The first was explored in Parts I and II, while the second branch (and elements of the third branch) were covered in Part III. In addition to these three ‘bigger’ branches, the last two decades have also seen the emergence of many ‘smaller’ branches, such as European external relations law, European labour law and European environmental law. And there now also exist specialised LLM courses on EU consumer law and EU tax law.

The list of journals (Table 21.5) is by no means comprehensive. It is meant to point the interested reader to a first gateway for an in-depth study of a particular part of European Union law. My selection focuses primarily on English-language academic sources. But it goes without saying that European Union law is a ‘European’ subject with journals and textbooks in every language of the Union.